The first time you buy a camera...

To re-appropriate a quote by Nicholas Cage, playing Yuri Orlov in “Lord of War” (2005): “The first time you buy a camera is a lot like the first time you have sex. You have absolutely no idea what you’re doing, but it is exciting, and one way or another, it’s over way too fast.”

Congratulations on accepting that you want a camera in your life! You are now entering the ranks of an “anointed” class of people with more money than sense who, by and large, spend too much time obsessing over their rapidly depreciating technological atavism and too little actually making images.

All jokes aside, I commend anyone who makes the leap and invests in image-making, be it photography, videography or filmmaking. Using a dedicated camera will change how you approach photography and video, and will give you an extremely rewarding means to reflect on the world and express your experience in it.

But, before you go out spending your hard-earned credits on a Mamiya 645 or Hasselblad X-Pan (which is what I would do if money were no object), you should probably ask yourself a series of questions. The answer to those questions should lead you to the “perfect camera” for you.

The following text represents a personal, unabridged thought process of selecting cameras - developed after more than 15 years from my first camera purchase. Whether you are a novice or a pro, looking for your first “real” camera or thinking of a change in your photography approach, there’s something here for everyone.

Do you actually need a camera?

An old adage goes along the lines of “the best camera is the one you have with you”, which I perpetually connect to the monumental Henri Cartier-Bresson. Many consider him the father of street photography, and he made photographic history equipped with his (at the time) amateur-grade Leica M3. Following that train of thought, since Nokia released the 7650, most of us have had some sort of camera in our pockets.

While for most of their history, camera phones and later smartphones were the poor siblings in the photon gathering marathon, in the last five years, they’ve made such improvements that even I struggle to tell if an image was captured on a phone or a “real camera” if I don’t go pixel peeping.

So, if you have just started your photography journey and have spent more than £600 on a phone in the last few years, you might have everything you need to start creating images. Your main goal should be to take control over the image-making process. So, put your image-taking device in manual mode and start learning how to explore the world around you through composition, exposure and colour. If you are unsure how best to use your phone as a camera, have a read through Jo Bradford’s “Smart Phone Smart Photography” and try creating your first few series without spending anything more.

Most people tend to ascribe good photography and video to “the best equipment”, but after more than a decade doing it and tens of thousands of pounds spent, I can assure you that technique, experience, and taste are 80% of what makes a good image. I would argue that for most casual photographers/videographers, a good smartphone used with intent and skill can deliver all that they need.

How should one pick a camera?

The first thing that will probably bewilder you when buying a camera is the sheer number of options you are presented with regarding brands, prices and form factors. There is a lot of myth, too much marketing, and an unhealthy level of almost religious zealotism in the camera world.

Canon shooters will tell you that the Canon R3 is the best thing since sliced bread, while Nikon shooters will boast how the Nikon Z9 will literally take the picture for you. To be frank, most big brands offer fantastic cameras if you spend more than £800 on a new body, which makes the choice even more complicated.

So, instead of approaching the camera acquisition problem from a technical marketing-driven perspective, let’s approach it for what it actually is: an art form, a profession, a hobby. What camera to get should be a philosophical, ethical and experiential question tied to the aesthetics of what and how you want to reflect upon the world around you.

You should ask yourself what and how you would like to photograph. For example, suppose your primary interest is shooting lush contemplative landscapes where you wait for hours or days staring at the horizon, waiting for the light and atmospheric conditions to be “just right”. The best camera for that is probably a medium-format film Hasselblad, Bronica, or a digital Fujifilm GFX100s.

If, however, your goal is to snap candid moments in the markets of Marrakesh while on your way to the next adventure, a lightweight APS-C camera with good AF and a fast and light 23mm f:1.4 prime that you know like the back of your hand is probably the best choice. With it, you can be inconspicuous and capture moments of honesty without your subjects becoming self-conscious due to the presence of a large and intimidating camera.

After you’ve achieved a modicum of technical proficiency, the embodied experience and connection with your subjects while creating the image will have a drastically more significant effect on the final photograph (or video) than the technical specifications of your camera.

What makes a good photography experience?

The photographic experience is subjective and starts with how the camera feels in your hands and on your body, how the image looks in the viewfinder or on the screen, how easily it is to trigger the shutter, and how appealing the sound it makes is. After ‘the decisive moment’ of the shot, the question becomes: how easily and intuitively can you obtain the image from your mind’s eye, either directly from the camera, or through subsequent analog or digital processing?

Some people prefer having a large-body camera with many buttons and features, while others want the stripped-down point-and-shoot experience. There are no right or wrong ways.

Some people will prefer composing their shots through an optical viewfinder, while others will consider having an articulating screen paramount, so they can more easily get high and low-angle shots.

Some image-makers will require the most cutting-edge, AI-driven phase-detect AF, 6K RAW Video Recording or blazing-fast sensor readout speeds, while others will want to slow down and meditate while they go through the “ritual” and contemplation that manual focus film photography entails.

The most important thing is to understand what you want your relationship with the creative process to be, what your strengths and weaknesses are, and only then pick a camera that makes the most sense for you.

When confronted with a plethora of similarly specced and similarly priced cameras, especially when you haven’t figured out precisely what your photographic interests are, pick a camera whose industrial design you find visually appealing. You will need to be carrying that thing with you everywhere in order to get good, and, as shallow as it might sound, you want to feel proud when you take it out of its bag because it is an extension of yourself, of your personal style.

What makes a good camera?

A good camera is a camera that empowers the user to create an accurate representation of their reflection of their subject, at any given time, with ease and haptic satisfaction. There are a plethora of technical factors that go into the creation of a technically sound image. Still, at the end of the day, a good camera and lens combination should produce an aesthetically pleasing image that can be presented in the creator’s desired medium without the artifice of its creation becoming apparent.

While absolute technical image quality is essential for a very narrow set of photographers doing reproduction, medical or scientific imaging, for the rest of us, the goal should always be to create images that tell a story, create a mood, excite the eye, inspire or emote.

Photography, Film and Video have always lived in a dichotomy between artistry and technology. While aesthetics and experiential aspects are subjective, the fundamental technical aspects, in which many get bogged down, can be easily simplified.

Image quality from a camera’s perspective can, whether captured into film emulsion, recorded electronically onto magnetic tape or stored as a file on digital media, be described by three characteristics: spatial resolution, dynamic range and colour resolution (colour gamut).

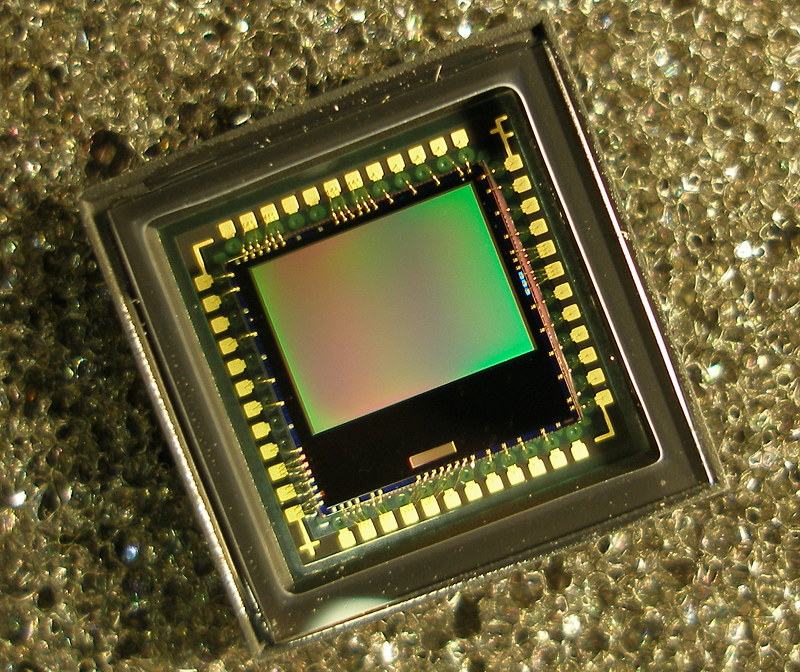

Spatial Resolution represents the smallest feature that an image can represent, assuming perfect optics (which don’t exist), which is, in turn, defined by the size of the film grain crystal or photosite for a given imager size. It is often expressed in “megapixels” (MP) in digital cameras and has been historically erroneously used as the sole consumer metric for camera quality.

Your choice of spatial resolution should be determined by where and how your images will be viewed. If you mainly publish to social media or YouTube, anything between 2 to 12 MP is enough. If you are printing, it depends on the print size and the printer’s DPI. Some huge museum-quality prints can require 50MP or more.

For film and video, you will generally want a ~3K (6MP) sensor to get a crisp 2K/HD image and a ~6K (22MP) sensor to get a crisp 4K/UHD image. In some video and cinema cameras, manufacturers use advanced algorithms to extract a 4K raster out of a ~4000 photosite wide Bayer-pattern-filtered CMOS image sensor (the standard sensor type in virtually all modern digital cameras). In my opinion, that is a slight cheat as it contradicts the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, which, while grossly oversimplifying, tells us that you can expect to get about 0.7 of the resolution of your RAW image in your final raster from a Bayer-filtered sensor.

I know some fantastic artists out there who still shoot on a 10-year-old Sony a7S I with its 12MP sensor due to its portability, superlative low-light performance and extended compatibility with vintage lenses, so it goes to show that pixel count is probably the least important technical part of a camera.

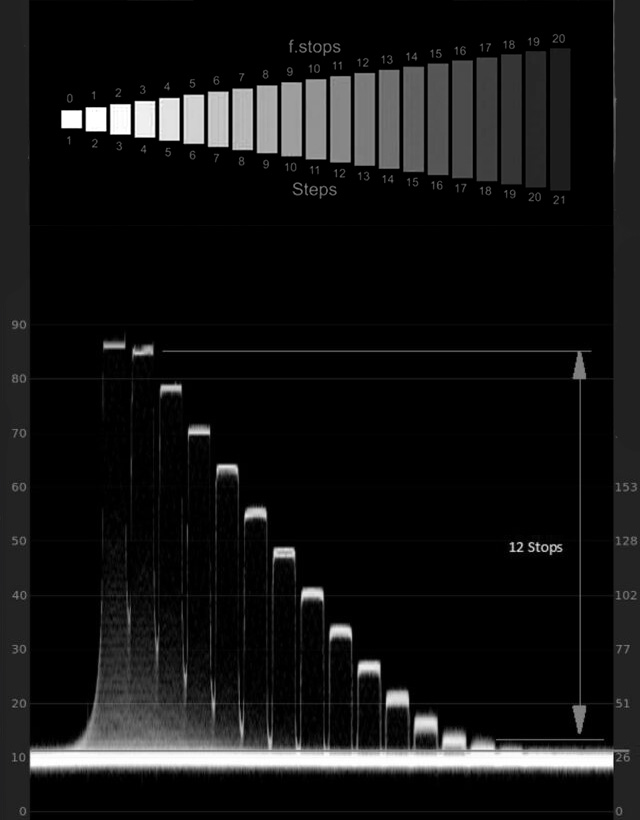

Dynamic Range is the ratio between the brightest and darkest parts of an image that a camera can record while retaining their detail in one exposure. In order to achieve pleasing results, you will want a camera that can record at least 10 stops of dynamic range.

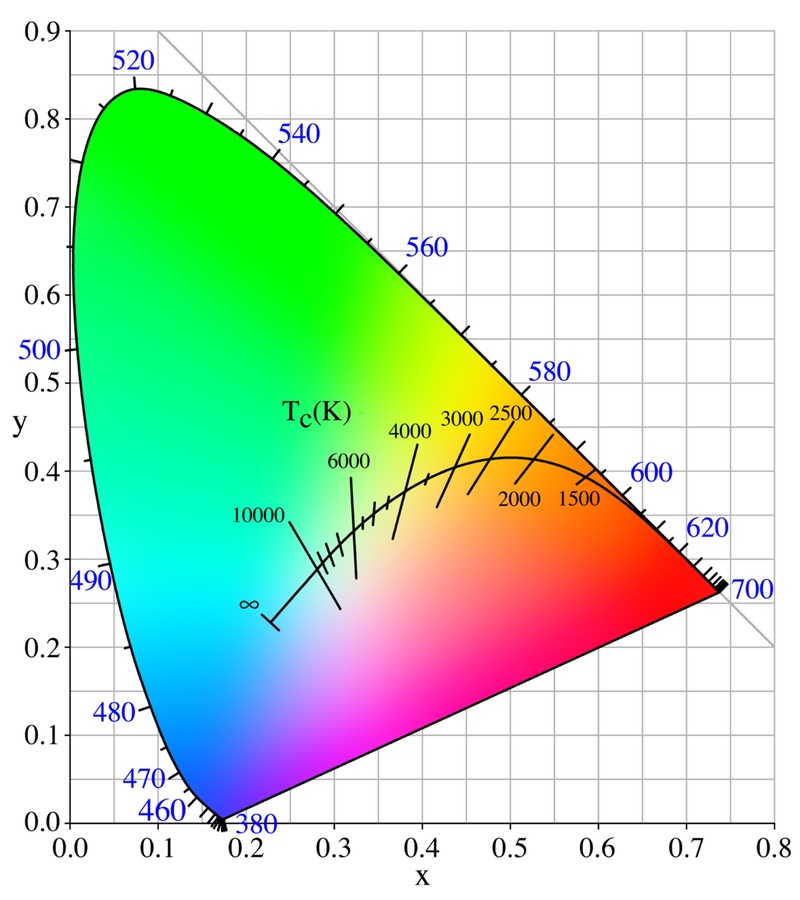

Colour Gamut is the total number of shades and hues a sensor or film stock can differentiate, and a display device can reproduce. Each camera has its own native gamut that can be loosely extrapolated from the bit depth of the file produced (the higher, the better).

If you are deeply interested in the technical side of photography, specifically resolution, dynamic range and other tech specs, feel free to consult repositories of camera data such as DP Review or DxO mark. I don’t find those particularly useful beyond comparing competing products, as the most important tests for a camera are the subjective ones.

Should I get a DSLR or a mirrorless camera?

SLRs and the DSLRs that replaced them have been the professional workhorses of the photographic world ever since their mass adoption in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but as the 2000s were coming to a close, many manufacturers started releasing rangefinder-style interchangeable lens mirrorless cameras.

In the beginning, these were niche products targeted at travel and street photographers who needed high-end performance in small and lightweight inconspicuous bodies. The trend continued through the early 2010s until Sony introduced the Sony a7 as the first Full-Frame mirrorless camera, which, with its subsequent revisions, variants and offerings from other manufacturers, completed photography’s transformation to a fully digital experience.

I am tremendously fond of the unique experience of composing through a pentaprism mirror viewfinder, where the light reflected by the subject is directly focused onto my retina through as little tertiary interpretation as possible. I use film SLRs whenever I want to slow down, contemplate, meditate, and rebalance my appreciation of photography.

That being said, professionally, I’ve given up on DSLRs as the image and exposure preview, weight-saving, and advanced autofocus features that mirrorless cameras offer are too good to be ignored for the sake of my poetic relationship with the image-making device.

DSLRs are fantastic “first cameras” at the moment, especially since they are currently flooding the used market. Due to their technical limitations, they force the user to slow down more, appreciate the shot and hone in on their craft gradually as they shoot, process the RAW files and repeat.

Many seasoned pros will keep their top-end DSLR for years to come as they are reliable, rugged, and produce outstanding images in their hands. But, as those cameras age and manufacturers slowly discontinue their DSLR lines (with the exception of Pentax at the time of writing), we are all heading towards a mirrorless world.

If you intend on buying a new camera, I can’t see any technical reason why you would buy a DSLR today - besides particular physiological and medical edge cases that have to do with motion sickness, ability to focus and eye fatigue.

Should I buy a film camera?

I can’t profess my love for shooting film enough. It has made me the cinematographer I am today, and it was the beginning of my photographic journey. Film photography is as pure of an experience as possible, and it encourages the shooter to be creative, deliberate and effervescent. Film is a very forgiving medium that can provide an emotionally engaging visual experience both in shooting and viewing with minimal post-processing.

As a learning tool, it provides a very steep learning curve when it comes to exposure, composition, and best practices that, once mastered, empowers the photographer to tackle any visual challenge.

To this day, I get a sense of absolute awe whenever I get the opportunity to develop and print in a dark room. Seeing an organic, vibrant image slowly emerge from the chemical bath is absolutely hypnotic.

That being said, the last five years have made it increasingly difficult to shoot film. Many cameras of the early to mid-90s (which can be seen as the apex of film camera technology) have started failing to the point of no return. The few models still being manufactured are not particularly good, and the cost of raw film stock has skyrocketed.

Shooting one roll of Kodak Ektar 100 35mm colour film will cost £12, then developing is £8, and high-resolution scanning (6700x4500px TIFF) is £15, or you can get basic prints for £8. Whichever way you look at it, it’s getting close to £1/ picture, which is a bit much to swallow for most people.

If you can afford it, do give film photography a try as it is the purest form of this art, but be ready to shoot very little or spend very much.

Do I need a Full-Frame camera?

A great deal of the photographic discourse of the last couple of decades has been taken up by the endless debate and posturing on the advantages and “absolute necessity” of using a Full-Frame camera if you want to be a serious photographer. While the mirrorless revolution has challenged that to a large extent, many still claim that Full-Frame is the only way.

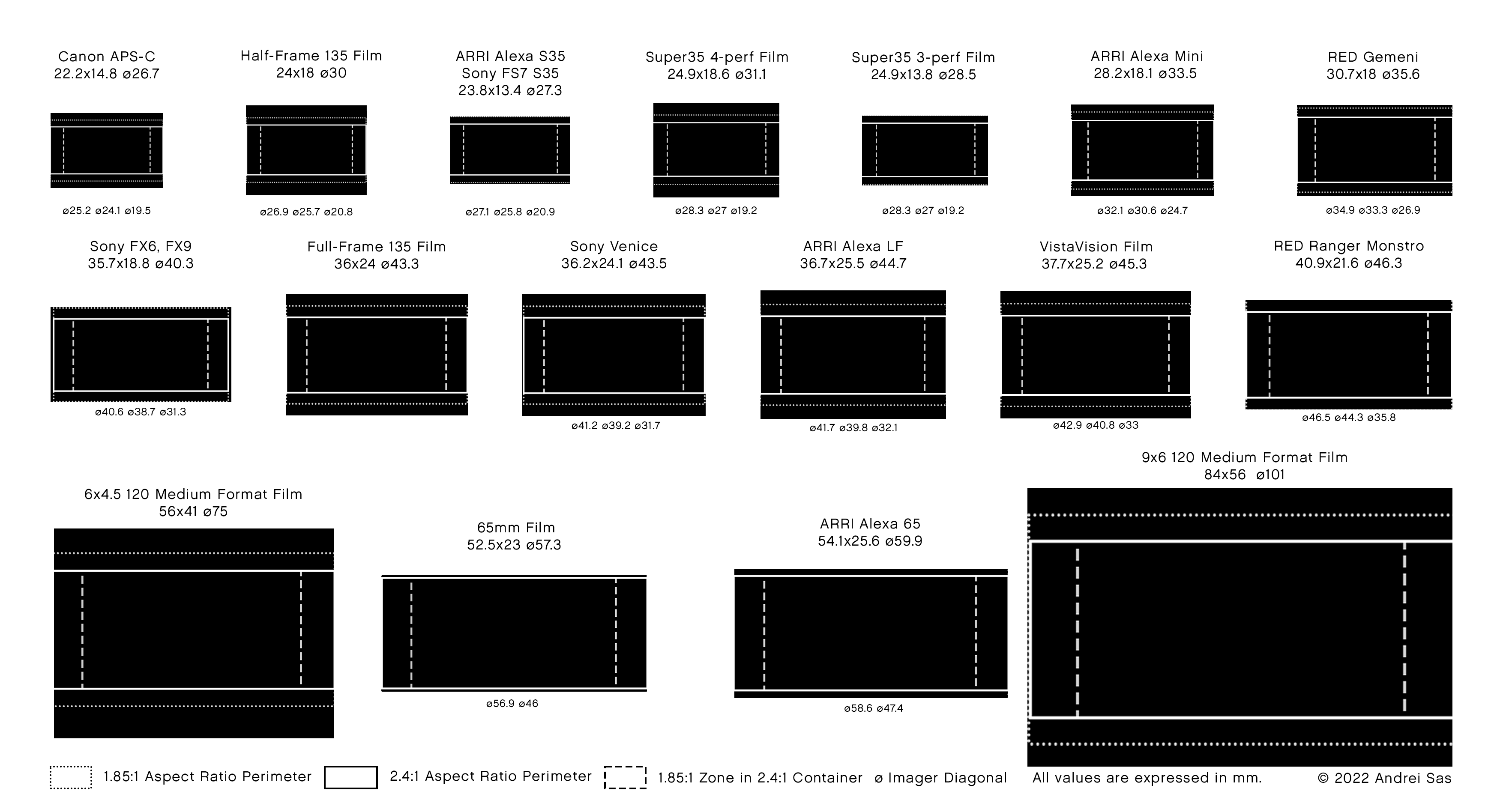

If I’m being slightly facetious, “Full-Frame” doesn’t exist. To be more precise, it didn’t exist as a term until the advent of digital cameras and the need to differentiate early models equipped with APS-C-sized “crop” sensors from the standard “Full-Frame” film gauge of the time. The “Full-Frame” film format, more accurately known as 135 film, is a Leica adaptation of the early 20th century in which perforated motion picture film stock was run through a photography (stills) camera horizontally in order to create a portable, easy-to-use camera that produces a negative that is 36 x 24 mm.

Until the 1950s, 135 film itself was considered an amateur “crop” format in relation to the medium-format professional cameras used at the time and their 84 x 56mm negative. As film chemistry improved and a desire for more organic and affordable photography emerged in the 1960s, many consumers and professionals alike adopted the format, becoming the standard way to create photographs.

Filmmaking started out on essentially 135 film from the get-go, which, with the advent of the Bell and Howell perforation, was solidified as the format known today as Super35 with a negative size of 24.9 mm x 18.6mm, which is “surprisingly” close to the 23.7 x 15.6mm negative size of APS-C. For all practical purposes regarding angle of view (AOV), depth of focus and “look”, Super35, APS-C and Half-Frame are interchangeable terms.

Thus, I would like to urge the reader, from this point forward, to avoid calling APS-C-sized sensors “crop” as it’s both historically inappropriate and creates an unhealthy bias in our mind that implies that APS-C is somehow “lesser”. One of the best image sensors on the market at the moment is the Super35 size Alev IV sensor in the ARRI Alexa 35.

It is true that, assuming similar diode technology, materials purity and manufacturing processes are used, a Full-Frame sensor with the same photosite count will, on average, have 1 to 2 stops more dynamic range and low light capabilities than its APS-C/Super35 counterpart due to the photosite being 1.5x larger on FF than S35, allowing for more light to be gathered on each, and more spread out, leading to less interference from adjacent photosites and better overall heat dissipation. So it should come as no surprise that the Full-Frame sensor in the Sony FX6, with its 8.3µm photosite, has more dynamic range and performs better at high ISOs than the Sony FX30, with its 3.7µm photosite.

In an ideal world, I would leave the “Crop” vs. Ful-Frame conversation at that, but in practice, most manufacturers do treat the APS-C sensor as their “lower-tier” offering and, as such, use cheaper-to-manufacture sensors in them. To my knowledge, notable exceptions are Sony’s Alpha 6000 line of cameras and Fujifilm’s X-T, X-E and X-Pro lines, which pack “Full-Frame” performance into compact APS-C cameras with no obvious cost-cutting observable.

To summarise, in photography, bleeding-edge performance will always be found in the flagship Full-Frame or medium-format cameras of each manufacturer. That being said, one should not easily disregard APS-C as a primary camera option. How much image quality is enough is subjective, bringing us back to one of the central themes at hand: aesthetics and usability.

Aesthetically, with Full-Frame, you gain:

-

a shallower depth of field for any given f-stop and AOV

-

a wider 1.5x wider AOV for any given focal length, which can enable you to get closer to your subjects, leading to even more background separation but also potential perspective distortion

-

in some edge cases, lens manufacturers can employ simpler designs for their “wide” lenses, which are less prone to optical aberrations, especially when coupled with short-flange mirrorless camera mounts.

APS-C camera’s advantages are:

-

smaller weight and physical size on average compared to an equivalent Full-Frame camera

-

lighter and more affordable lens selection

-

better suited for macro and nature photography, where the crop factor helps with image magnification

Full-Frame cameras are often more technically proficient and can provide better image quality than their APS-C counterparts, but they will not make you a better photographer, videographer or filmmaker. Don’t feel pressured by marketing and spec-envy to think that “unless you shoot Full-Frame, you are not doing it right”.

Should I buy new or used?

Whenever feasible, I advise buying used; your bank balance and the planet will thank you.

If you are starting out, you don’t need the latest and greatest camera, and you will benefit more from buying a model that is one to two generations old and investing what you’ve saved in better lenses. Most “kit lenses” (the lenses supplied with many prosumer cameras) are optical abominations made to the tightest of cost limitations.

Most professionals keep using their equipment even when it’s two or three generations old as long as it still does what they need it to do when they bought it. For them, it’s a business decision. The longer they can keep earning with a camera, the more return they will get on their original investment.

As a word of caution, if image quality is something you care a lot about, don’t buy anything older than a decade. Sensors have come a long, long way since 2013, and the images coming off most of the older ones are likely to be worse than a modern high-end smartphone.

My go-to place for used equipment is MPB. They always have a good selection, and while their prices are not the best (eBay will always be your best bet there), I trust that their cameras will have been appropriately checked, and that I will be able to return them if I’m not happy with their condition or functionality.

For film cameras, it’s trickier these days, especially when you don’t know the good makes and models, or how to check them. A good brick-and-mortar camera store would be my first choice, though some bank on their clientele’s lack of knowledge and practice unconscionable prices. Always compare the price for a particular model with eBay.

If, for whatever reason, you decide to buy a new camera, you should make sure that you will be okay to use that camera for at least 5 years. A cheap camera and a good one have very similar environmental manufacturing costs, so for all our sakes, please abide by “buy nice or buy twice”, as we don’t know for how long this planet can sustain our insatiable desire for new and shiny things.

What camera would you recommend?

Given all of the above, it should be apparent that it’s hard to recommend any one camera, but I will try to provide some options with the caveat that they are only valid at the time of writing and will be biased by my own experience, artistic philosophy and personal taste. As much as I try to be objective, there are platforms that I know better than others, and I am wary of recommending equipment that I have not tested myself.

Cameras that output great images without processing:

-

Fujifilm X-T4 - Buy Used @ £950 - APS-C Workhorse - excellent lens selection, great for video

-

Panasonic Lumix DC-S1 - Buy Used @ £850 - Great all-rounder with superb lens selection in L-Mount

-

Nikon Df - Buy Used @ £800 - Supports all F Mount Nikkor Lenses, great styling.

-

Fujifilm X-T30 - Buy Used @ £650 Compact APS-C with fantastic built-in film simulation and excellent lens selection

Starter Cameras:

-

Sony a7 II - Buy Used @ £600 - Excellent Full-Frame all-rounder, great lens selection, okay for video

-

Sony a6400 - Buy Used @ £600 - Compact APS-C with stellar AD, great lens selection, great for video

-

Panasonic Lumix G9 - Buy Used @ £450 - Micro 4/3 Sensor, Compact Lenses, great for video.

-

Nikon D750 - Buy Used @ £500 - A low-end Full-Frame professional camera with a fantastic lens selection.

-

Canon 5D Mark III - Buy Used @ £500 - Great look in camera, fantastic AF, decent for video.

-

Canon 80D - Buy Used @ £350 - One of the last great APS-C DSLRs, affordable, great third-party lenses.

Street Photography Cameras, where portability, concealability and ease of use are paramount:

-

Leica M10-P - Buy Used @ £4,000 - A worthy successor to the M lineage of cameras with a price to match.

-

Ricoh GR21 - Buy Used @ £1,500 - An inconspicuous Street Photography Classic

-

Sony DSC-RX1 - Buy Used @ £900 - A more affordable street-oriented option with a fantastic fixed lens.

-

Fujifilm X-E4 - Buy Used @ £900 - Fantastic travel camera with a great selection of lenses

-

Olympus Pen F - Buy Used @ £700 - Extremely portable and stylish with a plethora of compact, great lenses

-

Olympus OM-D E-M10 - Buy Used @ £300 - Great budget option that will deliver unexpectedly good results.

Landscape Photography Cameras, where image quality and resolution are the priority:

-

Fujifilm GFX 100S - Buy New @ £4,500 - as close as one can get to Medium Format Film.

-

Sony a7R IV - Buy Used @ £1,800 - Highest resolution Full-Frame Sensor, great colour, great lens selection

-

Nikon Z7 - Buy Used @ £1,000 - High quality, affordable mirrorless camera with a good selection of lenses.

-

Canon EOS 5DS - Buy Used @ £850 - One of the last high-resolution DSLRs, a great selection of legacy glass.

Film Cameras, where lenses and film stock are more important than the camera body, but body reliability is key:

-

Leica MP - Buy New @ £4,830 - The Cadilac of Film rangefinder cameras.

-

Olympus OM-1 - Buy Used @ £200 - Reliable mechanical cameras with fantastic lenses.

-

Nikon FM10 - Buy Used @ £150 - The last prosumer SLR to still be manufactured. (Until Pentax comes back.)

-

Canon AE-1 Program - Buy Used @ £100 - A reliable companion with a great selection of FD glass.

-

Pentax K1000 - Buy Used @ £150 - Fantastic first-time camera from the creators of the first Japanese Film SLRs.

-

Kodak Ektar H35 - Buy New @ £50 Half-Frame Double the Fun - Not a good camera, but fun to shoot and still in production.

To conclude, you have to sit down and meditate. Ask yourself: what kind of pictures do you want to take creatively? How do you want to engage with the camera? Do you want a more laid-back experience? Do you need an eyepiece? (You do!) Only after you have those answers you can determine what equipment gets you what you want.

And to bring it all back full-circle, I will end with the words of Henri Cartier-Bresson: “Your first 10,000 photos are your worst”. So you’d better just grab yourself a camera, any camera, forget the numbers, and start shooting!

Related Filmography:

-

Lord of War (2005) dir. Andrew Niccol

-

Blow-Up (1966) dir. Michelangelo Antonioni

-

One Hour Photo (2002) dir. Mark Romanek

-

Rear Window (1954) dir. Alfred Hitchcock

-

The Master (2012) dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

-

Secrets and Lies (1996) dir. Mike Leigh

-

The Conversation (1974) dir. Francis Ford Coppola

-

Super 8 (2011) dir. J.J. Abrams

-

Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005) dir. Miranda July

-

Boyhood (2014) dir. Richard Linklater

To get notified about future posts please follow the RSS feed or subscribe via email below: